Throughout my life, when faced with adversity, Ive often wanted to magically wilt either a cat or an Olympic athlete.

Cats are enviable considering theyre immune to worry and striving, and finger no pressure to succeed long-term projects. They are completely satisfied to bask in a square of sunlight on the carpet, or squat on a dresser like a Zen chicken, shimmer slowly and indifferently. It would be nice to have such a tropical structuring between ones natural desires and ones capabilities.

Ive envied athletes for similar reasons, although they tideway life very differently than cats do. Top athletes have well-spoken goals and a kind of inner momentum that seems worldly-wise to move them through vast amounts of pain and difficulty. On some level they must want to get up at 5:00am to throw medicine balls versus a wall. They want to run or ski or pommel-horse until their persons not their minds threaten to quit on them, if thats the forfeit of a shot at a gold medal.

I’ve never wanted a gold medal, but I’ve unchangingly wanted whatever quality it is that makes people want gold medals or anything — that badly.

Wanting to Want

Whenever interviewers ask an athlete how they endure training in the searing heat, or how they bounced when from a torn ligament last year, they unchangingly say, You just have to want it bad enough.

The follow-up question they never ask is, How do you get yourself to want it bad enough? I seem the athlete would shrug and say they dont know, they just do. Whether a goal attracts you strongly unbearable to incentivize pushing through every obstacle seems increasingly like a function of luck some natural attunement to the goal, or some inherited trait something you happen to be rather than something you choose.

I believe I was born with an unusually strong desire to eat sugary treats, for example. This desire has driven me to navigate the municipality solely to obtain a unrepealable Ben & Jerrys savor from a unrepealable grocery store surpassing it closes, and to eat it at 9:50pm plane though I know it will requite me horrible dreams well-nigh losing my teeth or my passport. I dont have to pulsate up the desire to seek this ice cream, or to endure any financing and consequences it entails. The momentum is intrinsic.

Meanwhile, psychologists tell me that my brains natural reward system is underactive, meaning that the prospect of conquering challenges and solving problems does not generate the same value of motivating reward-juice it does for the stereotype person. (It is moreover not uncommon with ADHD, they tell me, to react to that deficiency with dopaminergic vices like eating unshortened pints of ice cream.)

Thats not the end of the world considering I do have other talents and advantages. For one thing, Im pretty good at appreciating lifes ordinary moments (although I have had to work at that). I wouldnt trade places with the billionaire who can’t set whispered his desire to earn increasingly money long unbearable to enjoy a week-long vacation with his family. But I sure do wish I was dealt a bit increasingly of that trait we sometimes undeniability drive or tenacity the inclination to push through discomfort and wronging to the rewards beyond.

The gold medalists and billionaires among you may not understand this particular conundrum. Im sure some of you can relate, though. What do you do if youre not a naturally tenacious person? How do you become tenacious?

You just have to want it enough is a worldwide refrain but isnt useful advice, and in fact isnt translating at all, unless youre worldly-wise to tenancy how much you want things. Essentially its flipside way of saying, You have to be someone else, sorry. If sufficient desire is there, its there, and if its not, its not. The discus thrower who wants nothing increasingly than the time to throw discuses all night is in some sense lucky (or unlucky) to want that.

The Two Rewards

Recently I had an insight that might help you if youve unchangingly felt a similar deficit in the momentum or desire to overcome challenges.

I was journaling well-nigh the puzzler of self-motivation when I found myself having typed the line, One thing I do desire strongly is the feeling of relief I get without giving up on a tough problem. I have never exactly realized this, but I love giving up. I love giving up like I love ice cream. As long as I finger like I can somehow get yonder with it, I cant wait for that moment of releasing all effort and expectation, of unshouldering the heavy bag of grain onto the floor, of clapping the palmtop sealed and saying fuck it.

Looking back, I’ve been seeking this specific form of surrender-induced relief as long as I can remember, perhaps similarly to how Serena Williams seeks the feeling of winning tournaments and hoisting trophies.

Giving up, at least for the day, has unchangingly felt like salvation, a moment of release from the awfulness of having to do things you dont know how youre going to do. In my specimen this is undoubtedly a developmental side-effect of coping with undiagnosed ADHD for thirty-some years. Many of my memories of stuff a student or an employee were of stuff charged with an ordinary task that confounded me completely, and which most people virtually me could just do with no visible traumatization or trepidation. Escaping or delaying the task (while minimizing the fallout) often seemed like weightier performable outcome, and I got very good at that.

In other words, instead of learning to seek, as many people do, the glorious feeling of solving and surmounting problems, I learned to seek a related but variegated glorious feeling: the feeling of escaping having to do it.

Escaping vs Surmounting

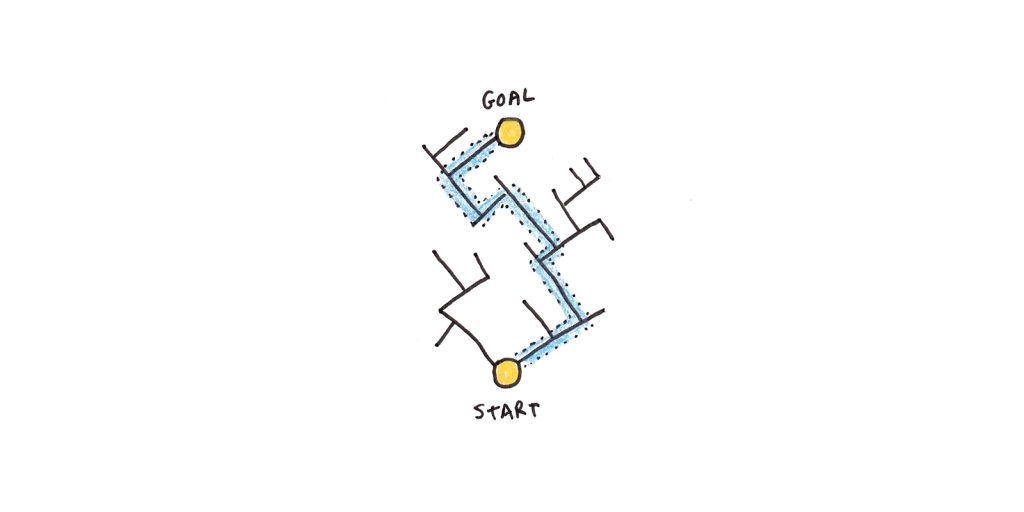

These two rewarding feelings — that of escaping the burden, and that of overcoming it — are cousins, each a result of a unrepealable shift in the effort unromantic to a stubborn task.

This unshouldering the burden feeling, the giving up feeling, comes from dropping the effort unromantic to the problem. You stop and surrender, releasing all mental and muscular tension, unsuspicious that you are not solving this thing, not today anyway.

The overcoming/surmounting feeling comes from seeing the task whence to unravel lanugo as a result of effort the exhilarating sensation of the knot finally loosening or the wall whence to topple. It often comes without pushing harder than usual, trying several variegated angles, or drawing creatively on your resources, rejecting all scenarios in which you dont solve the issue.

Both of these competing glorious feelings escaping and surmounting — are known to all of us. Some of us, for whatever reason learning disabilities, bad luck, bad mentors — have ripened a much stronger taste for the former. Our routines, plane our personalities, have wilt attuned to the escape feeling. Our hearts have ached for it and our expectations have been built virtually it.

For the chronic escaper, realizing the relationship between these opposing feelings creates an opportunity for recovery. The new game, as I understand it, is to stay as enlightened as possible of your fondness for the kicks of surrender, letting it remind you of the other, less familiar glorious feeling that is moreover available. You can uncork to consciously develop a taste for surmounting, while consciously reducing how often you indulge in the escaping feeling.

What we need to remember is that both of these rewarding feelings are misogynist at the exact same moments. Any instance in which youre tempted by the dropping-the-sack feeling, you could instead go for the toppling-the-wall feeling. They both finger good, but one makes the future largest and one makes it worse.

This new taste for surmounting can be ripened in small bits; you dont have to throw yourself into a PhD program or sign up for an ultramarathon. For example, when I squint at the clock and see theres only eight minutes left until quitting time, I’m tempted to waif the grain-sack right there and uncork thumbing through my phone, considering its only eight minutes so who cares. But plane this innocent move reinforces the taste for escape, for the valuables off of effort. A small taste of surmounting is misogynist in its place I can instead dial up the effort for that last eight minutes, and knock off some small task Id otherwise have to do tomorrow.

(This, in hindsight, is why a unrepealable method of working has been so powerful for me.)

More importantly, these small reversals make me a little less inclined to unshoulder the grain-sack at the first opportunity. The taste of surmounting likewise becomes a little increasingly appealing. The reward centers get a little increasingly used to that taste, and increasingly likely to momentum me towards it in the future.

I believe this is the way for the self-motivation hard-cases among us: to gently but steadily tip the wastefulness towards a taste for surmounting, by ramping up effort in precisely the places where we finger a starving to dial it back.

This process is what I now think of as tenacity. Plane the word itself tastes good.

***

Time to Learn to Meditate?

Raptitude is all well-nigh experimenting with ways to modernize the quality of your life. I’ve written well-nigh literally hundreds of variegated practices and perspectives, and nothing has come close to stuff as helpful as a modest daily meditation practice. It loosens the grip of bad habits and focuses the mind.

I’ve stuck with it for twenty years now, and I know I’ll be trying to get other people to meditate for the rest of my life.

I can teach you if you want. There’s still time to join this upcoming Camp Calm group — I don’t run them very often anymore.

The plan is simple: each day for thirty days we do a bit of meditation, and bring a bit mindfulness in daily life. By the end you will have your own self-directed meditation practice, which you can take as far as you want.

I’ll show you how to meditate and wordplay all of your questions. You can yack with other new meditators and old veterans in the discussion forum (aka The Campfire). You’ll have lifetime wangle to all 36 lessons and a ton of resources.

Also… it’s on sale right now. Ue the link unelevated to requirement it. Discount ends soon.

Photos by Graham Covington, Michael Sum, Jon Chng, Andrew Teoh, Simon Maage, Eduardo Flores, Leonardo Sanches, and Masaki Komori