One of the few lessons I recall from merchantry school is the make-or-buy decision. Big companies often squatter a choice: should they make something in-house, or outsource it to a supplier?

The visualization depends on many factors, but a big part is cost: will it be cheaper or increasingly reliable if you invest in in-house production? Or does it make increasingly sense to pay someone else to do it?

Decisions well-nigh whether or not to learn something are often similar. For scrutinizingly any conceivable skill you can:

- Learn to do it yourself.

- Hire someone else to do it.

- Avoid doing it entirely.

Consider programming. You could learn to write code, rent a programmer to do it for you, or segregate work and projects that dont require you to create software.

Or language learning. You could learn to speak Mandarin, rent a translator, or stave doing merchantry with monolingual Mandarin speakers.

The same nomination applies to myriad other skills, from understanding the tax lawmaking to applying medical advice, repairing drywall or planting a garden. You can learn, outsource or avoid.

Learning Rarely Makes Sense Short-Term

One worldwide full-length of this problem is that the financing of learning rarely make sense if youre only thinking well-nigh firsthand benefits. Plane if youre the smartest person on earth, hiring a Mandarin translator, Java programmer or car mechanic to deal with your problem still takes less time and energy than learning to solve it yourself from scratch.

Yet, if you once know how to solve a problem, doing it yourself is often (but not always) the most constructive option. Hiring people takes time, increases the possibility they wont understand or be worldly-wise to unhook what you want and can be increasingly expensive.

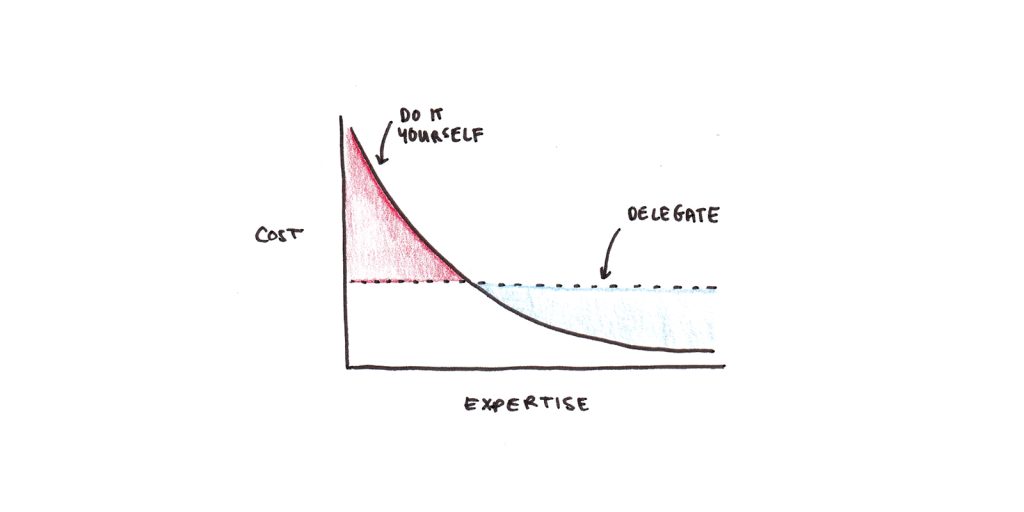

Viewed this way, the optimal point for many learn-or-delegate decisions depends on your prior expertise:

This wringer suggests you should do what youre good at, and consul what youre not.

The major wrinkle in this tideway is that your level of expertise isnt constant. It varies depending on the value of practice youve had on the problem. One of the most famous empirical results is the power law of practice, suggesting that many aspects of proficiency follow a roughly power-law relationship with the value of practice.

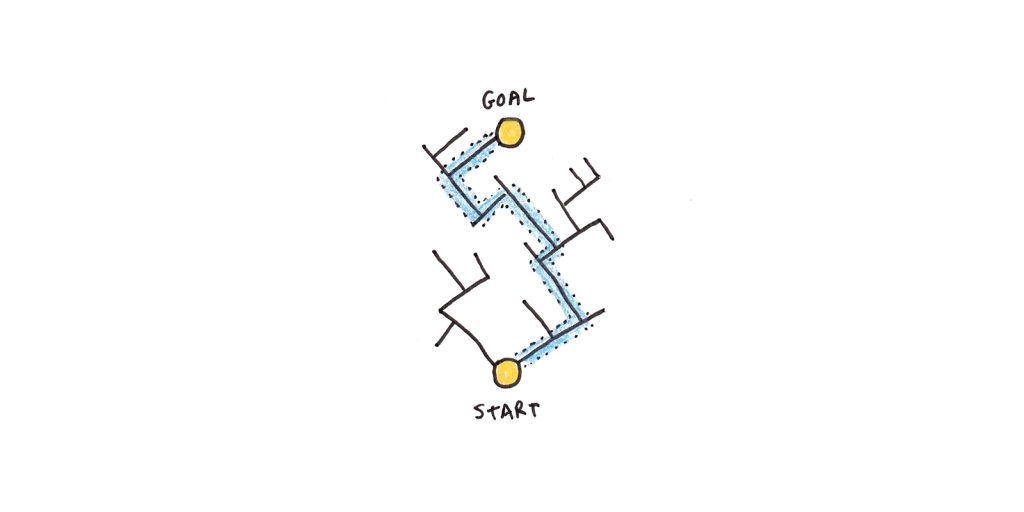

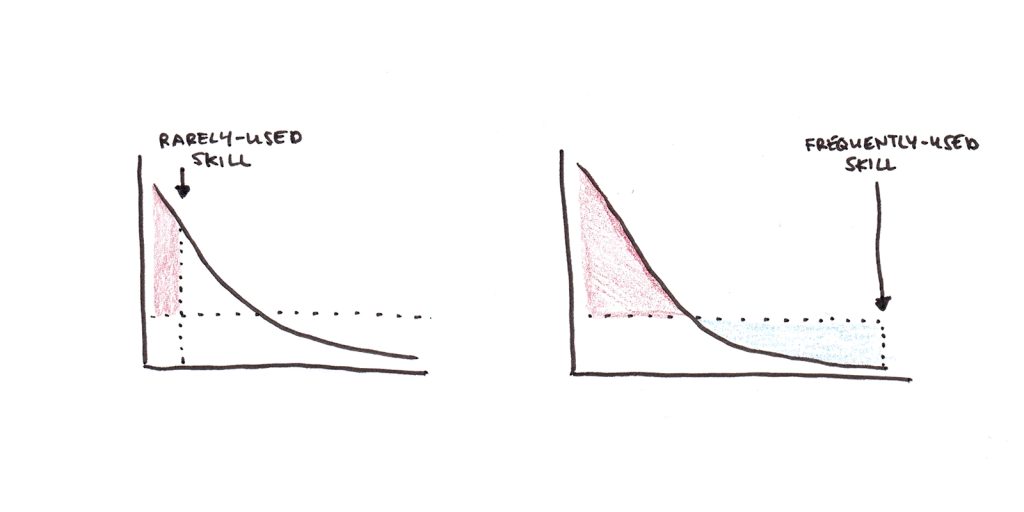

The wordplay to the learn-or-delegate visualization doesnt depend only on your current level of expertise, but moreover on how often you expect to perform the skill. If youre currently unelevated the competency threshold where doing it yourself makes sense but will probably use the skill a lot, the total lifetime forfeit of learning may end up stuff less than delegating:

While Im using an economic lens here, the reasoning still applies outside your job. How much I enjoy painting as a hobby depends on how good I finger I am at it. Thus theres often an implicit learn-or-ignore visualization with recreational activities that follows the same trade-off.

Do We Underinvest in Learning?

To summarize, many decisions well-nigh learning have the pursuit features:

- Doing it yourself doesnt initially pass a cost-benefit test.

- The increasingly you practice, the lower the forfeit becomes.

- Thus whether its worth it to learn something depends on a far-sighted numbering of how much youll need to use the skill.

Unfortunately our intrinsic motivational system is remarkably short-term in its focus. Firsthand financing or payoffs influence our visualization far increasingly than long-term ones. Experiments show people often pay steep unbelieve rates for elapsed rewards, in ways that are inconsistent with any rational wage-earner (even an extremely impulsive one).

This suggests we may be underinvesting in learning. Were disinclined to practice skills that goof an initial cost-benefit analysiseven if our investment of practice would be profitable over the undertow of our lifetime.

This insight helped Vat and me while learning other languages. The financing of practicing a language are relatively upper when youre not unceasingly using it. In the short term, forcing yourself to interact in a new language is moreover costly. But, if you practice enough, speaking the language of the country youre visiting becomes easier than sticking entirely within an English bubble. Adults are resourceful and commonly find ways to stave using an unfamiliar language; the magnitude is that few get anything tropical to the levels of exposure that young children cant help but get when learning.

Matthew Effects in Learning

Another magnitude of this vital model is that we should expect Matthew Effects in learning.

The Matthew Effect was first coined by sociologists Robert Merton and Harriet Zuckerman in their study of peerage scientists. Eminent scientists often get increasingly credit than unknown researchers for similar work, meaning that, over time, eminence tends to recipe while less famous academics linger in obscurity.1

Later, psychologist Keith Stanovich unromantic the same insight to reading. Those with a slight wholesomeness in early reading worthiness had a slightly reduced forfeit of reading new material. This lead to them practicing more, remoter reducing the financing of reading. Given the connection between reading and other forms of learning, he plane hypothesized that early reading worthiness might bootstrap intelligence by making it easier to reap new skills and knowledge.

Research bears out Stanovichs hypothesis. In a study looking at identical twins who varied in early reading ability, the slightly increasingly proficient twin later showed gains in intelligence compared with their genetically-identical sibling. Skills top-dress skills; knowledge begets knowledge.

Specialization and Focusing on Strengths

At this point, its helpful to clarify. Im not suggesting that since learned skills get easier with pactice, we should do everything for ourselves and never delegate.

This is false, plane by the vital logic Ive spelled out above. Some tasks simply arent encountered commonly unbearable to navigate the cost/benefit threshold. I may never have an opportunity to speak Mongolian, so if I overly meet a monolingual Mongolian speaker, Id be happy to lean on Google Translate.

Additionally, we cant consider skills in isolation. Spending time learning one thing is an implicit visualization not to learn something else. I could learn French, but that time is taken yonder from learning Mandarin. I could learn Javascript, but that time cant moreover be spent learning Python.

Ultimately, specialization, not self-sufficiency, is the road to zillions in the world we live in today. We consul the vast majority of skills in our lives, not considering learning them all is impossible, but considering getting really good at one thing makes sense when its relatively easy to consul everything else.

Despite spending years learning programming, I do virtually none of it for my own business. Given that my writing is inside to my business, and I dont have unbearable time to do all the writing Id like, hiring other people to do the programming makes increasingly sense. Those people, in turn, tend to be much remoter withal the expertise lines than I am considering theyve made a similar visualization to specialize.

That stuff said, there are many instances where skills cant hands be delegated. I might be worldly-wise to rent out behind-the-scenes programming for my website, but it doesnt save effort or forfeit to rent someone to read the research used to write the articles. If I dont understand the research, I cant weave it into the text Im producing.

In other cases, delegation is an imperfect or inconvenient substitute for stuff worldly-wise to do something yourself. Relying on a translator is not equivalent to stuff worldly-wise to speak the language yourself when you move to flipside country. Stuff worldly-wise to read a text isnt made redundant if someone narrates it to you aloud. Thus stuff worldly-wise to speak the language of the country you live in and stuff worldly-wise to read are skills that are scrutinizingly certainly worth mastering.

Thinking well-nigh Learning in the Long-Term

I find it useful to alimony in mind a few things when I squatter resistance to learning something new:

1. How much can I expect this skill to get easier with increasingly practice?

One way to estimate this is to squint at people with varying degrees of experience. How much effort did it take them to do what you struggle with? The learning lines is quite steep for some skillsyou get good relatively quickly. For others, the lines is unappetizing for a long timeyou may need to practice for years surpassing you finger its worth the effort.

2. How much would I use the skill if I was largest at it?

Supposing you could reach the relatively unappetizing part of the practice curve, how much would you use it?

If you live in a country that speaks a language you dont know, learning that language would definitely pass the cost-benefit test. Learning a major world language you might use in work or educational contexts probably moreover does. A niche language that isnt spoken much maybe not? In this case, it may only be worth learning if you have a strong intrinsic motivation to learn it.

If a skill is inside to your career, it may hands be worth the cost, plane if it is initially difficult for you to learn. In contrast, a career skill that doesnt fit well with your existing skills may go unused plane if youre nearly an expertits simply cheaper to outsource.

3. How much would I enjoy the skill, provisionary on stuff largest at it?

Economic rewards arent the only motivation. If youre good at something, you tend to enjoy it increasingly and yank personal satisfaction. But thats increasingly true of some skills than others. You might be particularly proud of stuff worldly-wise to paint a realistic landscape but not finger too special well-nigh stuff worldly-wise to file your taxes quickly.

Deciding when it makes sense to learn isnt trivial, but given that our intuitions often requite us a misleadingly short-term picture of whats possible, it can be helpful to think increasingly tightly well-nigh it.