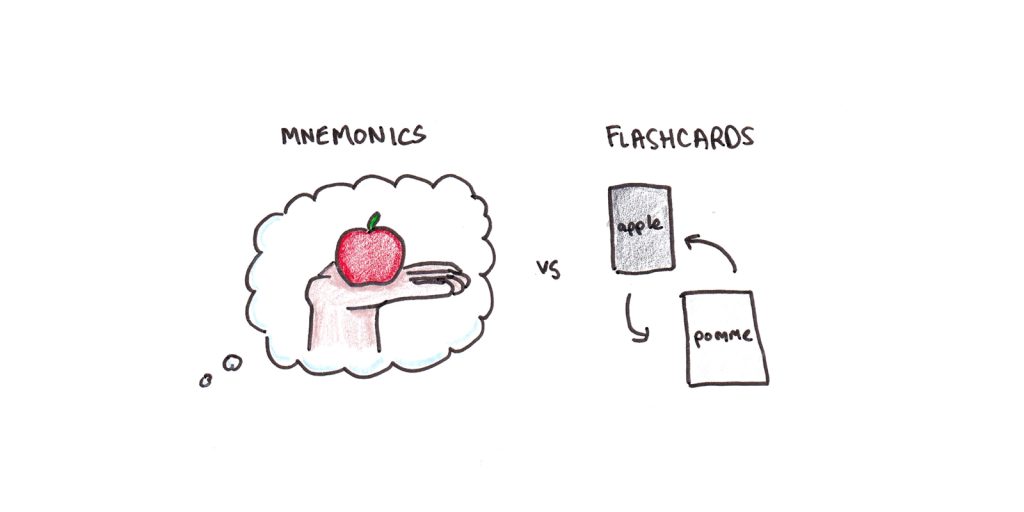

Suppose you have to memorize a lot of materialvocabulary words in a new language, terminology for an torso class, legal precedents, or dates of historical events. Which strategy will lead to largest performance: mnemonics or flashcards?

In the small and strange world of studying strategies, mnemonics techniques receive a lot of attention:

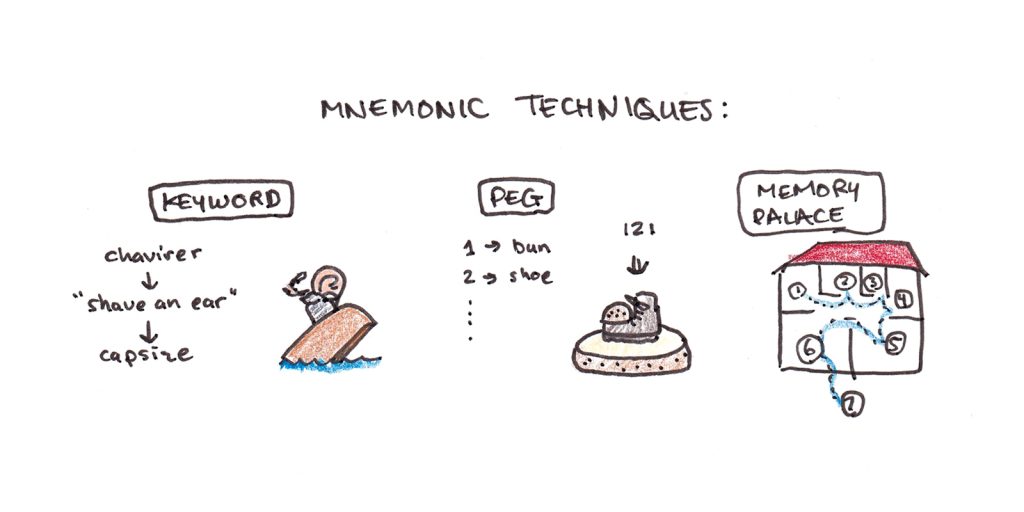

- The keyword method allows you to memorize a word by linking it through an intermediate and fantastical picture. The French word chavirer, which ways to capsize, gets transliterated into shave an ear, and you picture a villous ear shaving itself in a canoe thats tipping over.

- The peg method first links images to numbers (one is bun, two is shoe, etc..) and then combines these into elaborate visual imagery to encode and recall wrong-headed numbers and dates.

- The memory palace uses a mental stroll through a familiar location. You insert fantastical imagery withal a pre-remembered linear sequence, permitting you to graft wrong-headed information onto this prior structure.

In Moonwalking with Einstein, the writer Joshua Foer explored his swoop into peerage memory competitions, where people memorize the order of a deck of cards in under a minute, learn the values of pi to thousands of decimal places, or develop perfect recall of unfamiliar texts, verbatim, in only slightly increasingly time than it takes to read them.

Given these impressive results, starting with mnemonics for any skill that depends heavily on memory would seem a no-brainer.

In contrast, flashcards are, well, kinda boring. Everyone has washed-up them before. Theyre dry and elementary. You put a question on one side, the wordplay on the other and you drill (and drill and drill) until you can do them without thinking. No fantastical imagery or secret method. Just repetition.

Flashcards are Underrated

While mnemonics might seem like the obvious nomination for learning a ton of new information, research rigorously comparing the efficacy of various studying strategies paints a somewhat variegated picture.

In their spanking-new review of ten popular studying techniques, Dunlosky and colleagues summarized the research on both the keyword mnemonic method and practice testing (which includes flashcards). In this review, practice testing got the highest possible rating for usefulness, while the keyword mnemonic got a low grade.

The keyword method does workthat is, students who use it tend to remember the words they were memorizing largest than those who didnt. But it had a number of limitations:

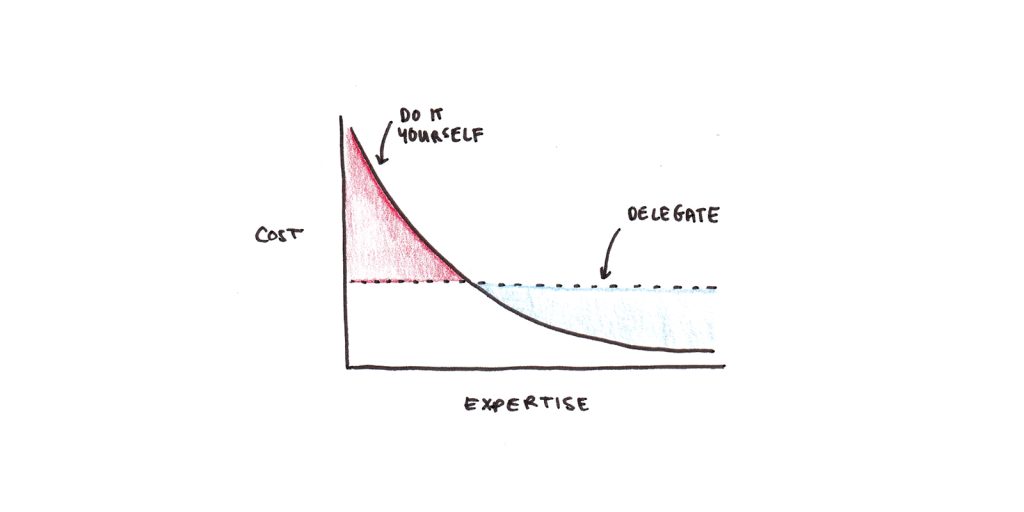

- It takes time to learn and teach mnemonic methods. Unlike flashcards, mnemonics is itself a skill that requires considerable practice to get good at. While this may goody peerage mnemonists, it may not be worth the spare investment for those who simply want to learn Spanish, law or anatomy.

- Mnemonics often take a good deal of time, expressly for beginners. It may take a few minutes to create a good link with the keyword method, in which time you could have washed-up several repetitions with flashcards. One study, which equalized the time-on-task between mnemonics and increasingly rote memorization, found that simply increasing repetition provided an wholesomeness over using the mnemonic.

- Mnemonics profoundly squire with recall over relatively short intervals, but their benefits might not endure. This makes mnemonics useful in memory competitionsevents that require memorization of highly wrong-headed information with near-immediate recall. In contrast, much of what were trying to memorize needs to stay in our heads for much longer.

Flashcards, in contrast, are simple and quick. While all memory fades eventually, the repetitive overlearning caused by flashcards is one of the increasingly durable ways to create long-term learning.

Direct Retrieval is the End Goal of Learning

Empirically, mnemonics are a bit of a mixed bag. Flashcards seem to have the advantage, at least in thoughtfully controlled studies of longer-term recollection in students who arent once trained in mnemonic techniques.

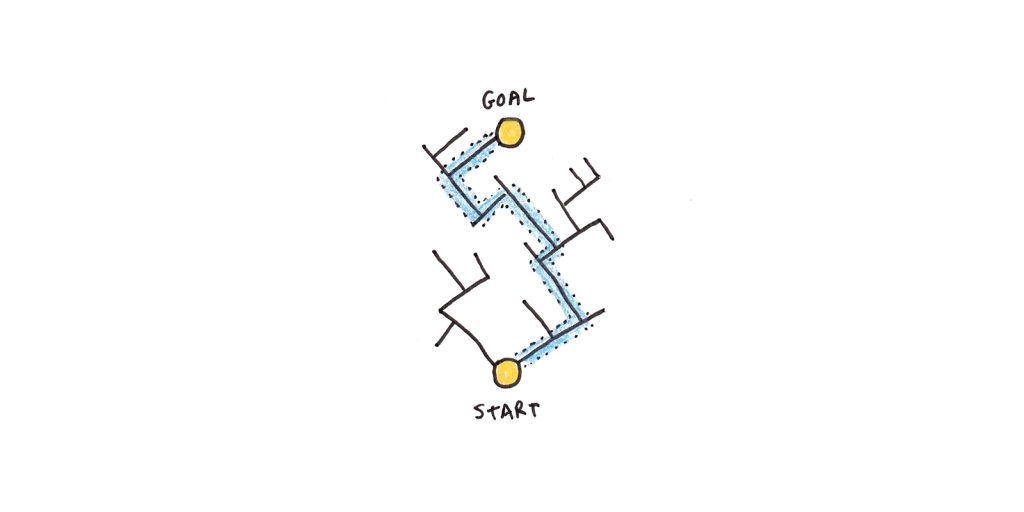

Cognitive theory moreover lends support to this perspective. A major full-length of skill vanquishment is that the methods used to unzip a result are not constant. For instance, children learning simple wing start by counting both numbers on their hands, then count from the worthier number and finally retrieve the wordplay directly.

As expertise develops, increasingly elaborate methods tend to be replaced by uncontrived retrieval of the answer. This is one reason that expertise can be relatively effortlessinstead of going through an elaborate process to get to an answer, you just remember it.

Mnemonics, in this light, can be seen a little bit like the finger-counting. The vivid imagery acts as a underpass between two concepts that would otherwise be difficult to associate. You can quickly learn the mnemonic and it enabling you to navigate over from one idea to the other. However, if you practice enough, the two ideas get directly associatedwith no intervening imagery.

For situations where fluency is particularly important, such as recalling vocabulary words while speaking, the uncontrived retrieval option is perhaps necessary for a majority of words in order to not get bogged lanugo while speaking too much. This suggests that plane if you initially learn a word via mnemonics, uncontrived retrieval will sooner take over as it becomes the faster option.

This suggests that mnemonics are, at best, a temporary measure. They may make learning an undertone easier, in the short-to-medium term, for words that havent been sufficiently overlearned to form a uncontrived association.

Why Not Both?

Of course, flashcards and mnemonics are not mutually exclusive. You can use the keyword mnemonic when you first encounter a flashcard and then study it repeatedly. In this way, the temporary underpass offered by the mnemonic may be salubrious to learning.

This is the tideway Ive used when Ive had to memorize a lot of material. I start with the keyword mnemonic, when that is relatively easy to do, and follow with a lot of spaced retrieval practice to make the undertone will-less and robust.

However, I think its worth examining the relative efficacy of the two techniques for a few reasons:

- Many people get overly excited well-nigh mnemonics and use them instead of flashcards. I think this is often ill-advised for the reasons Ive articulated above.

- Sometimes the material isnt mnemonics-friendly. I found the keyword mnemonic unconfined for learning vocabulary in European languagesbut far less helpful for Asian languages. The sounds like method doesnt hands discriminate between words in Chinese (which all sound like each other much increasingly than they sound like words in English) so the first leg in the underpass is weak. However flashcards unfurled to work and were my primary tool for learning Chinese and Korean vocabulary.

- For those not trained in mnemonics, its worth asking how much time should be invested in acquiring the skills needed. While mnemonics have some valid use cases, they are often slow and cumbersome without lots of practice, meaning they are weightier reserved for situations where theyre likely to be used wideness many memory-intensive subjects.

In short, if you are proficient with mnemonics, by all means, use them to supplement your flashcards. If youre not, or your subject makes using them difficult, or you simply arent sure which one to prioritize, stick with the flashcards.